Over ten years ago (around 2012) when I first started researching sex testing I encountered something that vexed me. A specific claim made over and over again in scientific papers: the “fact” that black people are more likely to be intersex than white people. Or, sometimes, more specifically, the claim that black Africans were more likely than any other group to be intersex.

The first time I read this, I stopped. Why would that be true? Certainly there are cases in which specific genetic conditions are more prevalent in certain populations. Tay-Sachs Disease is more common among Ashkenazi Jewish folks. Sickle cell disease is believed to have evolved as a defense mechanism for malaria, and thus is more common among people with ancestry in high malaria zones like South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.

But being intersex isn’t the result of a specific, singular genetic mutation, like Tay-Sachs. It’s a huge variety of genetic configurations with all sorts of root causes. And intersex variations don’t correspond with a specific adaptation, the way sickle cell disease does. Plus, Africa is a huge continent, with an incredible amount of genetic diversity. The idea that Africans in general would be much more likely to be intersex just didn’t make sense to me. And so, like any good science journalist would, I looked at the citations.

What followed was a maddening game of citational nesting dolls. One paper would cite another, which would cite another, and down the line. Not a single one of these papers provided any supporting evidence for this claim beyond the fact that someone before them had published it. And more than once, this game of citational chase wound up depositing me right back where I started — authors citing one another, back and forth, until the end of time, with no primary source to be seen.

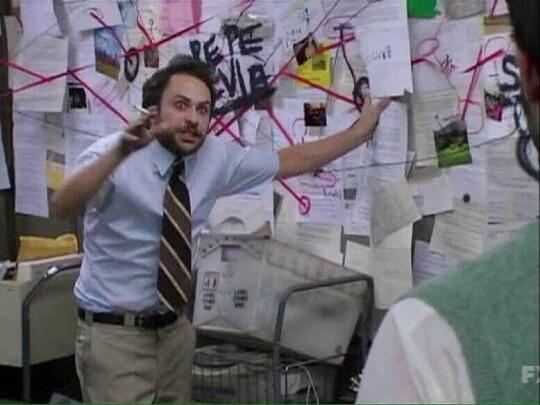

Soon, I became a journalist possessed. Not a single person in my life was unaware of this issue. I ranted about it at length, huffed and puffed in my office, and I asked every source I interviewed where this idea came from. Most of them weren’t sure.

Eventually my madness led me to a citation for a masters thesis from 1970, by a researcher named Hatherley James Grace titled “Intersex in Four South African Racial Groups in Durban.” This seemed to potentially be ground zero for all of these claims that I had been seeing. There was just one problem. The paper itself did not find an increased prevalence of intersex conditions in black Africans. “The overall impression gained from this work is that there is little difference between the frequency of intersex in whites and Bantu,” Grace writes in the conclusion.

Surely, I thought, I had to simply be missing something. Certainly a whole slew of papers were not repeating a fact based on this fifty year old masters thesis that did not even prove the fact in the first place. Eventually, for the sake of my sanity, I set this aside and went on to report other pieces of the story.

Then, in 2023, historian Amanda Lock Swarr published her book Envisioning African Intersex, and it was as if all my nerdy academic dreams had come true. It turns out we had been similar quests — although hers was far more wide reaching into the history of this question. Swarr’s book looks at the history of claims around gender, sex, and race all the way back to the very beginnings of colonial expansion. It’s a really fascinating book and I definitely recommend it if you’re interested in reading more.

You hear Swarr for a teeny moment in Tested (in episode four), but our conversation was so interesting that I wanted to bring it to you! So here is an edited excerpt from our chat (also, any typos or grammatical errors you might see are my fault, not Swarr’s):

Rose Eveleth: How did you get interested in this topic?

Amanda Lock Swarr: I first encountered this topic through the claim that black people were more likely to be intersex than white people in medical literature from the 1970s, based in South African medical journals. And I found it really disconcerting because there was no evidence given. So I could see that the claim was being made, but I didn’t understand the grounding.

So I began looking for the origins of this claim. And the further that I dug into the question, the further back I went. And so I ended up in my research 400 years back, finding early representations of African African people’s bodies by colonial explorers… diaries and written accounts, and especially drawings.

Colonial drawings were not based on observation, they were exaggerated and often based on imagination. So these were not accurate representations, and they were full of biases. But they tended to be repeated, and they were brought from colonial locations back to Europe. And despite how exaggerated they were, despite how monstrous they were, they were accepted as fact.

These claims and these illustrations were repeated again and again in countless accounts. They made their way into textbooks. They made their way into the origins of modern science and modern medicine, and they were incorporated into medical literature. And what I was most astounded by was that these really old claims from 400 years ago, about African intersex, were accepted despite their the holes in their origins.

And so, in my own work, I wrote about these citations, which I call “citation chains.” The repetition of citations — which science is really based on. Science is based on building on work by other folks. And claims of black intersex became kind of linked in these chains that actually spanned centuries.

Rose: When you say certain claims from 400 years ago, can you be more specific? What claims are you talking about, what were people saying?

Amanda: So early explorers were looking at African folks’ bodies, and they were especially interested in looking for difference. And this became the basis for theories of what we think about today as scientific racism — the theory that black people’s bodies are physiologically different from white people’s bodies. Sometimes we hear this talked about in terms of blood and bones and skulls — they were represented as different size and different compositions. It also manifested in the ways that genitals were represented.

So African people’s genitals were represented in really problematic ways as inherently different. And let me be clear: all these claims were false. But those representations of African genitals as inherently different and abnormal and inferior and monstrous became the basis for claims about disproportionate African intersex that continue to the present.

Rose: There’s also a section in your book where you talk about earlier ideas of what “intersex” even means. How has that definition changed over time, and why?

Amanda: So in the late 1800s scientists were kind of trying to figure out how to understand who was intersex and who was not. And in that moment intersex became so broadly defined that increasing numbers of people started to identify as intersex. And some scientists in Europe in particular were unsettled by this — the fact that intersex numbers were growing so vastly, and that so many people were were identifying as intersex or being defined as intersex, that the clarity of distinctions between men and women was becoming really blurry.

And so there was a push at this time to redefine who was intersex and who was not. And at the time that was really based on whether or not someone’s body had “testicular tissue” present in it. So the only way that someone could be diagnosed from that point forward was through some kind of surgical examination, or through death. And remember, at the time, surgeries were not common because anesthesia hadn’t been introduced.

So this meant that all of a sudden only corpses or people who were presenting in really explicit ways could be identified as intersex. So the numbers of intersex “true hermaphrodites” — that was the term at the time — dwindled down to almost nothing.

At the same time there was an interest in colonial science and trying to find intersex in the global South. And so scientists kind of started doing all this research on folks’ bodies outside of Europe and North America, looking for evidence of this so-called “true hermaphroditism.” And there was also an effort to expunge the records of true hermaphrodites, or intersex people, in Europe.

That took a lot of forms. Throwing out old studies, a discrediting those studies, declaring them kind of null, invalid, you know, could be throwing them out altogether, you know, potentially burning books. Research that was being done was declared unscientific was stricken from the record. Books were no longer cited that included this earlier definition of intersex that was seen as too broad and threatening.

And this is because colonialism is really grounded in the idea that sex differentiation — a clear distinction between male and female — is evolutionarily superior. So the more clear distinctions are between men and women, then the more advanced and civilized people are. So there was this kind of erasure of intersex existing at all in Europe and North America and an effort at “discovery” of intersex in colonial contexts.

Rose: Often when we read claims made in scientific papers, we just kind of accept them. Because these are the experts, and this only works if we trust that they’ve done the research. How did you know to question this claim about higher prevalence of black intersex folks when you encountered it?

Amanda: So from 1948 till the early 1990s, apartheid took place, and it was really based on racial science. So I had a skepticism of any kind of science or medicine that came out of South Africa in that era. And, you know, when I look at statistics, I always want to know, what’s this based on? And particularly when we’re looking at statistics around intersex, it’s really difficult to make any kinds of claims. Because most of the claims are based on observations. They don’t include folks who never see the doctor. They don’t include folks who are okay with their bodies. They include people who are presenting to the doctor for a particular reason.

There’s also lots of different definitions of intersex or DSD, as some folks like to call it. This can include 60 different diagnoses. So many of the studies actually, compared apples and oranges, right. There was no clear comparison across what was intersex.

Plus, a lot of ways of diagnosing what’s referred to under the rubric of intersex or DSD are really invasive. So they include surgeries to see what kinds of reproductive organs folks have or what’s happening in their body. They include testing of chromosomes and, hormonal tests. And so this is why it’s hard to make any statistical claims, because there’s no way to do testing en masse of big groups of people to even make statistical claims, especially when we look at how complicated intersex and DSD really are.

So with that in mind, I was really interested in the question. The question that says, “why are black people more likely to be intersex than white people?” Why is this question the right question to ask, and particularly why were so many studies undertaken to answer the question of that already assumes that black people are intersex? So I guess I really wanted to get to the origins of like, why are we asking this question? And why are all these failed studies being continually cited? Like, where does that leave us in this conversation?

Rose: Okay so let’s talk about those “citational chains” you mentioned. When you started digging, what did you find? Where does this citational chain begin?

Amanda: The first study I came across with a master’s thesis from the 70s that made this claim. And I was so confused because this thesis became the basis for assertions that continued from the 70s until the present. I think there’s often an assumption that if a scientific claim is being made, then there’s some basis for it, right? There must be some study. But I think we sometimes forget that ethical standards change over time, and what kinds of things are accepted as truth really change over time. And so what was accepted as truth in the 70s, and what was accepted as truth in the 1600s is very different from what we accept as truth today.

Rose: Wait let’s talk about this thesis because I also found it and I just assumed that this couldn’t really be the key paper! Can you say more about this paper?

Amanda: So the master’s thesis was written, in the 1970s by a student at the University of KwaZulu-Natal in zoology, whose thesis was based on the assumption that black people are more likely to be intersex than white people. And his hope was to find some reason for that. This was in the height of apartheid, and so he came into this work with this assumption that there were differences and he tried to prove that. And what was really interesting was that he couldn’t prove it. And he went to great pains to figure out why he couldn’t.

So what he ended up doing was critiquing other scientists saying “they’re using different definitions of intersex,” or “they’re not surveying the right people.” And he was very frustrated because he wanted support for his hypothesis in his proving of disproportionate frequency of black intersex. But in the end, he was very disappointed and he couldn’t prove it. And so his his conclusion is very dejected, saying, you know, of the hundreds of folks who he was able to include in the study, there were just a handful of folks who may have been intersex, and he was very dejected by the end of the thesis.

But then he himself became very prominent in genetics and in science, and in science that was really grounded in scientific racism. And he went on to then repeat the claim and cite his own thesis along with work that was more prominent. And if you went back to the origins of his own work, it never proved what he based his whole career on asserting.

Rose: You talk in the book about all the reasons that H.J. Grace and other researchers have trotted out about why they can’t prove this idea. Can you talk about those?

Amanda: The rationalization and justification was one of the most startling parts of the research, I think. When folks were unable to find proof or evidence for disproportionate black intersex then they would often go to a space of blame. So they would blame folks for not presenting. They would blame them for not going to the doctor more often. They would pathologize the fact that they accepted their own bodies, or that their communities accepted them as they are. Or they would say “we would have more evidence of our assertion that black people are disproportionately intersex if black people were more likely to present themselves. If African folks were more likely to or more willing to share the realities of their lives. So it’s because of their own secrecy that we don’t have proof.” And I think that was really jarring to me to see the the mental gymnastics that people undertake to provide a rationale and justification for why their own studies fail.

Rose: Okay this is probably a silly question but given that we can now look at this research, look at the words on the page, and see that this has never been proven… why does this continually still get stated as a fact?

Amanda: I mean, that’s a great question, right? Why do scientists rely on each other so heavily? I think is one question. Another is the way that scientific literature, and scientific claims get taken up in the mainstream. So this claim was not just confined to the pages of medical journals. Part of what I found is the way that it was repeated in the media. It was repeated in museums. It was repeated by athletic regulators. It’s repeated in the contemporary moment by athletes.

So it sort of takes on a life of its own where no one’s really interested in an objective analysis of the rigor of the original work. They kind of take it as fact, and it moves outside of a scientific context into a popular context where it it it gains strength, and it just becomes very accepted. And I think it’s really problematic. It’s a bigger question that we have about truth and science, and how we come to understand things as fact when often they’re not based in any kinds of realities.

Rose: This is another silly question but why does it matter? Why does it matter that this claim keeps being repeated without any real evidence?

Amanda: I’ve thought a lot about why this matters in the present moment, and I’ve been asked that a lot. “Why does this work from the 70s, or from the 1600s, why is it important now?” I think because it is the basis of these contemporary claims that have very real effects on people’s bodies and on people’s experiences. There are very real material effects of this claim that are leading folks to experience being banned from athletics. That are leading them to be coerced into medical practices that are unnecessary, that have devastating effects on their lives. So these claims are not just historical artifacts, but they impact people in the present moment, right? They keep people from participating in sport. They subject people to violent medical practices that are unnecessary and scrutiny of their bodies and banning from athletics that, disrupts and changes their lives for the worse.

So I think we really need to think about and interrogate these old claims because of their impact on contemporary athletics and because we care about what’s true. Right? I think we care about how we understand racism in medicine, and we care about really trying to reverse the wrongs of the past. I think that’s really important to all of us. And so it’s important for us to really think more carefully and be more cautious in our claims.

Read More

You can read Envisioning African Intersex for free online! If anything in this newsletter piqued your interest, I really recommend it. It’s fascinating and enraging and full of really important research.